Swiping Right on Tigers by Nicholas Budler

Posted in 2020 The Gnovis Blog | Tagged applications, apps, communication, social media

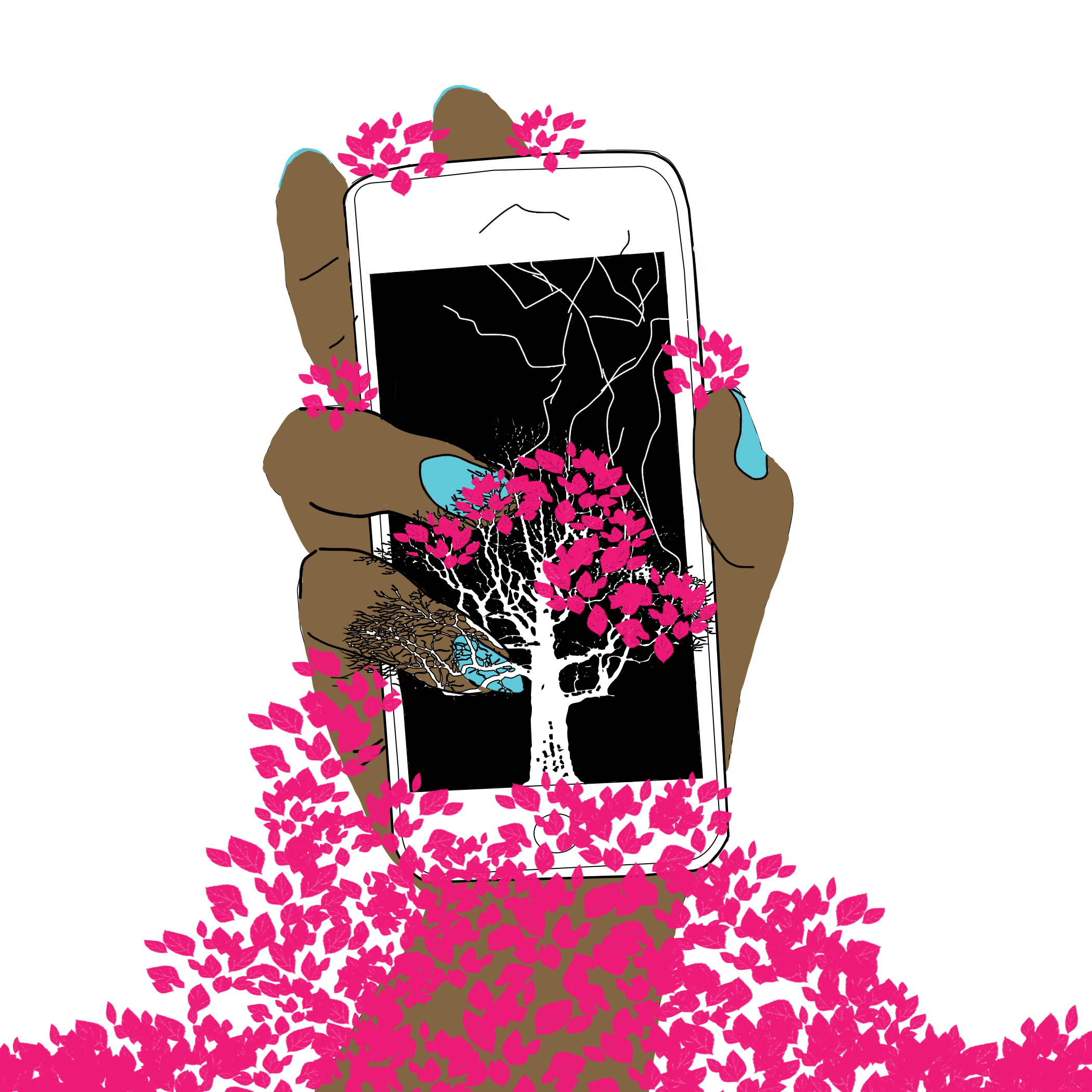

Using social media to promote digital conservation

Conservation technology might be the least sexy “tech” out there. Taylor Lorenz never writes about it, it doesn’t seem to show up on my LinkedIn feed (which is full of tech bros), and new advancements rarely make headlines in a political climate that downplays science.

Tracking collars, camera traps, drones, and crowdsourced data collection should be more important as a mainstream topic. They are, after all, protecting our planet in times when cascading natural disasters are on the rise, climate change has become an undeniable fact of life, and political leanings define environmental policy rollbacks.

The situation is improving, though. The fancy answer is that “the conservation community’s embrace of computational technology, and the passion, ingenuity and perseverance that a hugely diverse group of individuals and organizations have brought to this space is immensely inspirational, and the media and public have been paying attention…” (Lucas S661).

But nobody I know has read that paper (please DM me if you have, I bet you’re cool). Meanwhile, most young people have seen the viral video of the turtle getting a straw pulled out of its nose. It got millions of views on social media.

The unprecedented challenges of 2020 – Washington, D.C. is the wrong side of the country to be seeing wildfire smoke – combined with the rapid digitalization of our lives means there is no better time to push for advancements in digital conservation. Social media is the next frontier.

Access to Experts

Social media has decreased barriers to entry around talking with experts directly: Twitter allows direct replies, Reddit has AMA, and every platform has a DM function. These functions make it easier than ever to have a direct conversation with an expert–especially those who are regularly publishing (or Tweeting) their live data, photos, and updates from the field.

These platforms are extremely useful in meeting people where they are: online. The challenge becomes beating the algorithms of the Internet and raising awareness about experts in conservation who are often overshadowed by the sale of TikTok, the newest hashtag, and Lorenz’s latest piece in The New York Times.

Finding New Applications

The wider applicability of conservation tech is another reason to push for more investment and creating greater awareness online. For example, elephants in Kenya are equipped with SIM card collars and farmers get text alerts when they come too close to a particular location. The next question is: Where else can we use this technology?

There are a variety of ways that tech in other sectors and digital conservation can be put in conversation with each other. Twitter and Reddit, for example, are places where everyone can contribute new ideas, offer suggestions, and collectively solve problems if there are open-source options available.

In order to use it elsewhere, though, people need to know the tech exists. Organizations have taken their branding onto social media, a few examples being Wendy’s, Denny’s, and Netflix. Digital conservation efforts would benefit from these digital strategies in building brand awareness with a younger generation (Digital Engagement Associate at the National Audubon Society isn’t the only digital conservation job posted on LinkedIn).

Increasing Accessibility

A sizable challenge in the conversation around complicated tech is how best to communicate importance and use to a general audience (Scheufele). WWF, for example, offers excellent guidelines on camera trapping, acoustic monitoring, and remote sensing with LIDAR. While they do go on to discuss more complex elements of the technology, which largely went over my head, they begin with an overview that is helpful to anyone trying to get a better understanding of the basics. Writing like we speak will be key in bringing awareness to Gen Z on TikTok and other laypeople on Twitter and Instagram.

On the other side of the discussion, social media can be used to bring out the voices of underrepresented leaders in digital conservation who might otherwise not get a seat at the table or a platform for sharing their research. For example, the WWF hosts webinars and documentary screenings about Indigenous conservation leaders and activists while Twitter is giving a platform and voice to groups of emerging leaders.

What’s next?

Researchers have noted that, “Digital technology increasingly influences the ways members of the public perceive, think about and engage with nature…” (Koen S662) and this, when combined with the help of algorithms, potential for virality, and strength of social media movements, can be a powerful driver for change.

The idea would be to raise awareness about the importance of digital conservation–and the benefits and challenges–in order to create a surge in online support, donations, and more collaboration from the public and from researchers at a critical time for conservation of the planet.

Better understanding how to reach people where they are, as the turtle video highlighted, is necessary to accelerate change: “Maybe a few hundred scientists read the peer-reviewed article, whereas millions of people saw the video. Which had the bigger impact?” (Figgener).

Arts, Koen, et al. “Digital Technology and the Conservation of Nature.” Ambio, vol. 44, 2015, pp. S661–S673., www.jstor.org/stable/24670997. Accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Figgener, Christine. “What I Learnt Pulling A Straw Out of a Turtle’s Nose”. Nature.Com, 2018, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07287-z. Accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Joppa, Lucas N. “Technology for Nature Conservation: An Industry Perspective.” Ambio, vol. 44, 2015, pp. S522–S526., www.jstor.org/stable/24670985. Accessed 15 Sept. 2020.

Scheufele, Dietram A. “Communicating Science in Social Settings.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 110, 2013, pp. 14040–14047. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42713429. Accessed 16 Sept. 2020.