The Culture Industry: ‘Clean Girls,’ Coastal Grandmothers, and TikTok Consumerism by Riley Tinlin

Posted in 2024 The Gnovis Blog | Tagged Aesthetic, Algorithm, consumerism, culture, TikTok

By Riley Tinlin

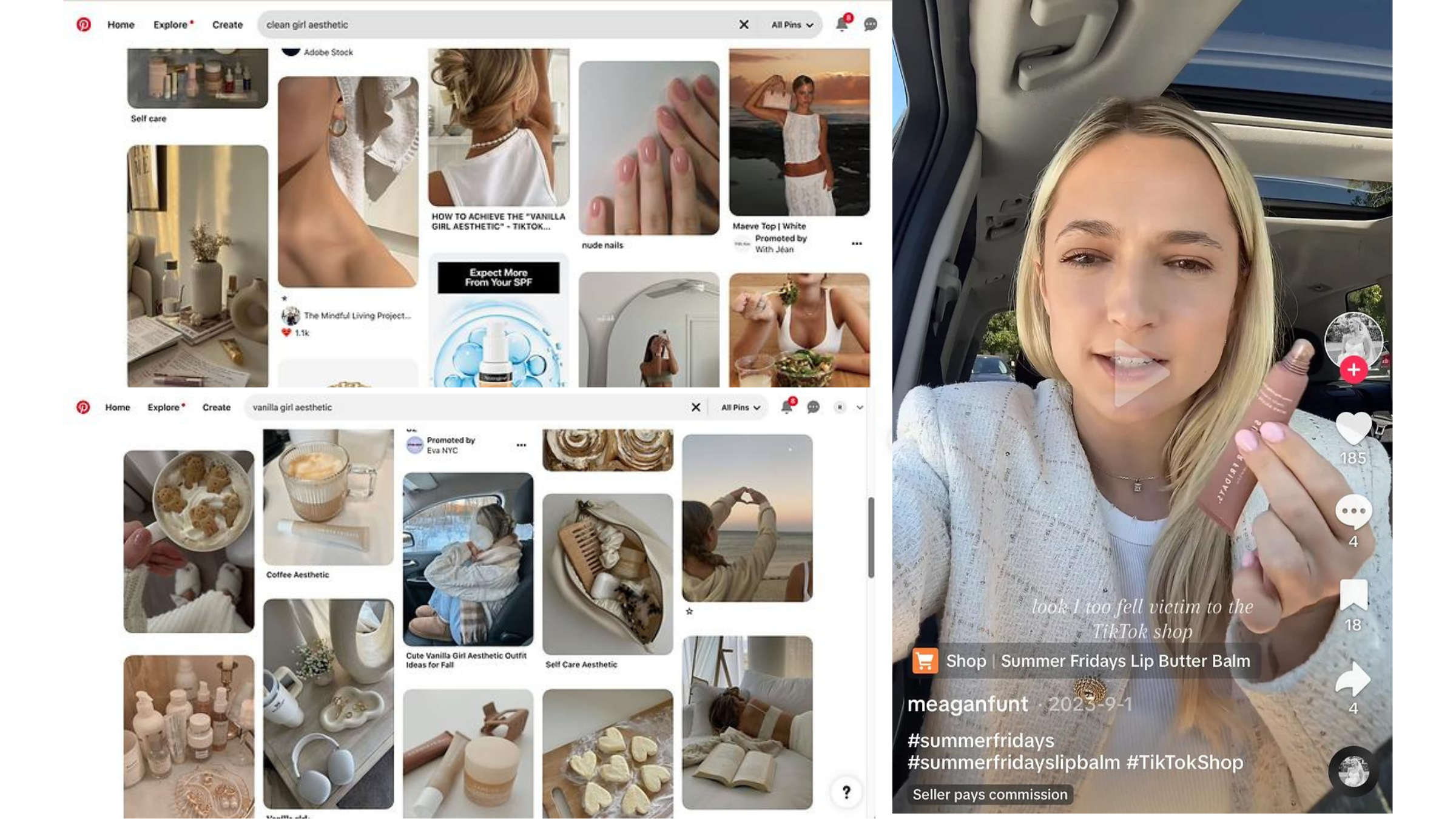

Every morning, I wake up and immediately open my phone. I know it’s a bad habit, but I can’t seem to break it. More often than not, the very first thing I do is open TikTok. As I scroll, I’m bombarded with the newest microtrends: Hailey Bieber has debuted her new “Cinnamon Cookie Butter” hair—and it’s perfect for fall! The Clean Girl aesthetic is out—Vanilla Girl is all the rage. Here’s a seventeen-step routine so you, too, can have Bella Hadid’s perfect glass skin. Are you more of a glazed donut-nail girl or a blueberry milk-nail girl? Are you siren-core or fairy-core? You must try the new sleepy-girl mocktail that’s changing my life! The comments are flooded with people eager to spend their next paycheck to hop on the latest trend before it fades into irrelevancy. No one wants to mention that the ‘effortless’ image they’re trying to maintain takes hours to curate or that by the time your TikTok Shop Summer Friday lip gloss arrives, it will be two weeks past due. No one wants to mention that these micro-trends are just slight variations of a ‘recurrent and rigidly invariable’ archetype. While “the details are interchangeable,” the outcome is the same—conform to the aesthetic of the week and buy whatever product is being touted or risk social isolation (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1947, p. 3).

Aesthetics have become a cultural product; staying on trend is a full-time job. Upon first glance, the sheer amount of different labels one could use to classify their aesthetic appears as evidence of a hyper-individualized cultural landscape—but as Adorno and Horkheimer point out, “in the culture industry, the individual is an illusion… what is individual is no more than generality’s power to stamp the accidental detail so firmly that it is accepted as such” (Adorno & Horkheimer, 1947, p. 18). I argue that TikTok is a perfect example of standardization through mass-produced culture. There are two things that most, if not all, of these aesthetics have in common:

1) You are more than likely to have to buy something to adhere to them, encouraging a consumerist approach to beauty. 2) The pinnacle is a rich, thin, blonde white woman who is the perfect picture of the Western beauty standard.

While certain aspects of these cultural products may appear unique, they’re carefully curated to reinforce broader social norms and values. This illusion of individuality is nothing more than that—an illusion. While the ability to choose whether to identify as “coastal-grandmother core” or “cottage-core” may provide consumers with an “artificial impression of being in command,” the real power is not aesthetic or even social but economic.

Adorno and Horkheimer argue that the rise of the Hollywood starlet created a phenomenon where “the girls in the audience not only feel that they could be on the screen but realize the great gulf separating them from it” (1947, p. 13). TikTok makes this gulf increasingly apparent. While the ‘democratizing’ algorithm of the platform gives the idea that anyone can go viral for anything at any moment– notice who is always at the forefront of these trends. And beyond that, who stands to benefit from them? Certainly not the individual.

TikTok has become the new mouthpiece for the conglomerate, spoken in pretty shiny words by girls who claim to be just like you. We become convinced that by participating (both socially and economically) in these trends, our identity will be validated. Still, instead, we are left unfulfilled, perpetuating a constant cycle of passive consumption and alienation. Not only do we become alienated from our own lived experiences, but we become alienated from society and community by being spoon-fed, a sanitized version of reality held up by constant consumption and the commodification of experience. Even I, a preacher from the soap box of the predatory nature of these trends, often fall victim to them. Adorno and Horkheimer’s concept of ‘assembly-line character of the culture industry’ creates an assembly line of homogenized pseudo-individuals who are “compelled to buy and use products even [when] they see right through them” (1947, p. 24).

References

Adorno, T., & Horkheimer, M. (1947). The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception. In Dialectic of Enlightenment.