Perfecting People, Pt. 2

Posted in 2011 The Gnovis Blog

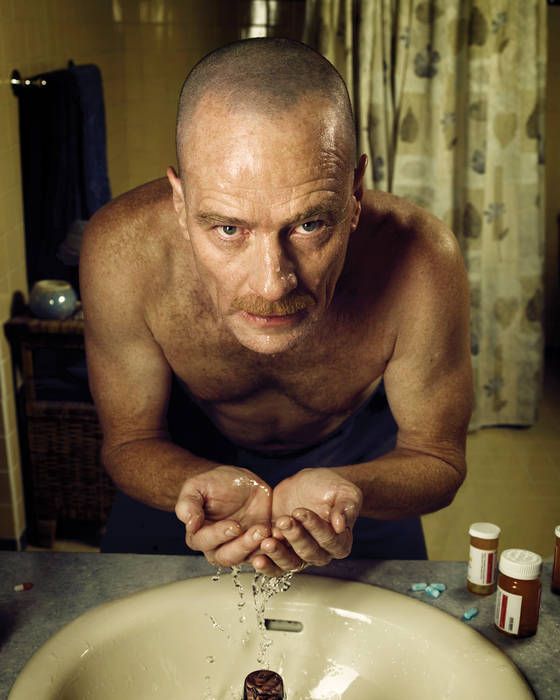

Truly, we can already see glimpses of the Singularity in the rise of social media, with academia, entertainment, government and industry still struggling to police it. And yet, there is a quieter argument against techno-perfection. Anyone who watches AMC’s Breaking Bad will recall the scene when, after improperly disposing of a dead body in a tub of acid , Jesse and Walter have to clean up the mess with sponges and soap. (Don’t ask. Just watch.) It ends with Walt, tortured, flushing a bucket of disgusting red goop down the toilet as he thinks in voiceover, “There’s got to be more to a human being than that.” Presumably, the same thing that makes liquefying a human being so loathsome is the same thing that might be lost or destroyed when we enhance ourselves with machinery or super-pills.

But, to use terms in Radical Evolution, will The Curve result in a “Heaven” future or a “Hell” future for us as it redefines humanness? Garreau ask a number of scientists this question, but the most interesting respondent is inventor Ray Kurzweil. Sixty-three-year-old Kurzweil, who so believes in the Singularity’s imminence he pops 200 vitamins a day so he can live to see it, relates The Curve to evolution, in that it’s an unstoppable “force of nature” governed by billions of little things we couldn’t control if we tried. Kurzweil thinks The Curve will lead to mostly positives for humanity, and when you see things like this — a “skin gun” that heals severe burns by creating new, perfect skin in an hour and a half as opposed to weeks — it’s hard to side against him. But even Garreau says the “essence of The Heaven Scenario is stealing fire from the gods” (106)—and, lest we forget, Prometheus’ story ended quite badly.

But, to use terms in Radical Evolution, will The Curve result in a “Heaven” future or a “Hell” future for us as it redefines humanness? Garreau ask a number of scientists this question, but the most interesting respondent is inventor Ray Kurzweil. Sixty-three-year-old Kurzweil, who so believes in the Singularity’s imminence he pops 200 vitamins a day so he can live to see it, relates The Curve to evolution, in that it’s an unstoppable “force of nature” governed by billions of little things we couldn’t control if we tried. Kurzweil thinks The Curve will lead to mostly positives for humanity, and when you see things like this — a “skin gun” that heals severe burns by creating new, perfect skin in an hour and a half as opposed to weeks — it’s hard to side against him. But even Garreau says the “essence of The Heaven Scenario is stealing fire from the gods” (106)—and, lest we forget, Prometheus’ story ended quite badly.

The Hell Scenario is very Terminator-like: it involves machines that become self-replicating and so smart they destroy us, supplant us as the earth’s supreme intelligence, and are helped along by myopic scientists who view themselves as neutral when they are in fact obligated to speak up when risks outweigh rewards. Neither Garreau nor I think technology is inherently good or bad; there must, however, be a reason every scientist knows the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who famously quoted the Bhagavad-Gita and said, “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds,” after seeing the first A-bomb test in Alamogordo in 1945. Secretly, we probably all side with Garreau—agreeing with neither the Heaven camp nor the Hell camp, simply wishing “we could just create better humans” without all the ethical fuss (273). But technology is never that easy. Mostly, it’s just weird—so weird we dismiss such-and-such thing as impossible until it happens.

Continued from Perfecting People, Pt. 1