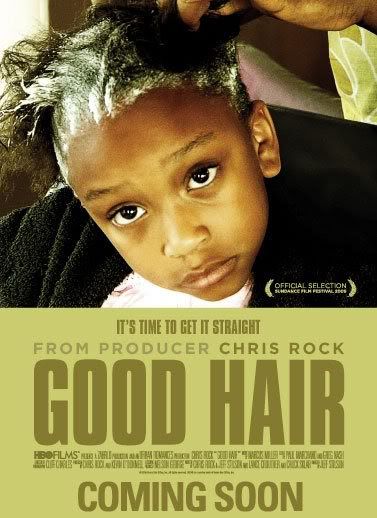

Good Hair, Bad Hair

Posted in The Gnovis Blog

Chris Rock reportedly settled on the topic of his latest film project after his 5-year-old daughter, Lola, asked him, “Daddy, how come I don’t have good hair?” It’s an interesting and complex topic, but not one that we haven’t heard about lately, which is why perhaps I didn’t enter the theater expecting what turned out to be a key critical text about race in the United States.

Chris Rock reportedly settled on the topic of his latest film project after his 5-year-old daughter, Lola, asked him, “Daddy, how come I don’t have good hair?” It’s an interesting and complex topic, but not one that we haven’t heard about lately, which is why perhaps I didn’t enter the theater expecting what turned out to be a key critical text about race in the United States.

Good Hair explores the culture around Black people and Black hair with considerable depth, covering perms, weaves, hair shows, beauty salons and barber shops. The initial volley is mostly predictable; in the United States beauty is largely based on a white ideal – a reality I, personally, have been hyper aware of growing up biracial and deriving considerably privilege from my “passing” features. So this recapitulation is important even for those of us who have heard it before, and I think even the most seasoned veteran will be struck by the novel packaging – e.g. little girls as young as five who may be permanently damaging their still-developing scalps with sodium hydroxide but still prefer to have their hair permed so that they can “be pretty.”

What takes this documentary to the next level, however, and makes it perhaps more interesting for people involved in Critical Race Studies is the analysis taken up around capital, internationality, and community. The examples are many including the increased difficulty in procuring employment for women who wear their hair natural and the changing dynamic of the Black hair industry as products are decreasingly generated out of a “for us, by us” ideal, shifting the profits from Black-owned companies to larger corporate conglomerates.

I was especially impressed by the segment in which Chris Rock visits Tamil Nadu, India to visit the largest source of human hair used in the creation of weaves and extensions in the United States. The investigation of how Indian women come to be parted with their hair – shaving their heads for religious reasons, voluntarily selling their hair to supplement depressed incomes, having their hair cut off and stolen in cinema houses – very interestingly begins to map the lesser discussed connections between oppressed peoples in South Asia and Black Americans. The other international angle, however, was unfortunately explored less explicitly – the hair-centered linkages among the diverse people of the African diaspora. The film does a good job of bringing out the voices of African immigrants and Caribbean people in addition to African Americans, but they didn’t necessarily speak specifically about the linkages and disjunctions these identity lines might create.

The film also does not shy away from sexuality, which as a queer person whose academic interests prominently include sex was refreshing. I was impressed by the frank discussion of the way weaves and extensions remap black women’s bodies such that the level of intimacy involved in touching a woman’s hair during sex has a drastically different cultural meaning than for most others.

Ultimately, though, my utmost admiration for this film springs from the fact that it so skillfully walks the line required for this kind of criticism between a very real critique of the racialized capitalist system that keeps black women investing their hard-earned money in “good” hair and resisting the temptation to strip them of their agency altogether. After all, even given the considerable social forces at play, black women should still be empowered to make decisions about their own bodies, seek out pleasure, and form communities for themselves.