A Mediated Log, Secular Sermon, and Marking Capitol Time

Posted in The Gnovis Blog

This is my first gnovis post regarding my master’s thesis topic, the weekly presidential address or formerly known as the weekly radio address. A genre of presidential rhetoric that developed during the Reagan administration, the weekly address has evolved from a strict radio format to an internet video channel under President Obama. I am examining both content and effects to study whether the transition to a different medium is altering messages and persuasive effects. Today, I am concerning myself (and you luckily) with the content side. I have found that in order to chart any change, one must have a template or foundation to work from first. This requires constructing a genre out of disparate speeches.

Genre or generic criticism grew out of a classifying need to group rhetorical acts together under a broad title. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell and Kathleen Hall Jamieson argue that a genre of rhetorical acts are united by an underlying “constellation” of forms and strategies including substantive, stylistic, and situational forms. Within this constellation are recurrent lines of argument, commonplaces, or what ancient rhetoricians called topoi. In other words, there is an internal dynamic that unites the elements. Therefore, the task of the rhetorical critic becomes identifying the dynamic that unites the constellation.

After examining 30 Saturday presidential addresses from the first year of President Bill Clinton’s, George W. Bush’s, and Barack Obama’s presidencies, I proceeded to begin looking for the underlying dynamic characteristic of all the addresses. This genre, I argue, is unique in that it is a guaranteed time each week the president speaks to the populous. Therefore, it is ritualistic and occurs like clockwork every Saturday morning. Additionally, I selected the speeches randomly at the same points during each first year (for example randomly selecting the 9th, 15th, and 21st week speeches for all three presidencies). With close examination, I found several common traits that make this genre of presidential rhetoric unique compared to the inaugural, State of the Union, veto message, or farewell address just to name a few.

After examining 30 Saturday presidential addresses from the first year of President Bill Clinton’s, George W. Bush’s, and Barack Obama’s presidencies, I proceeded to begin looking for the underlying dynamic characteristic of all the addresses. This genre, I argue, is unique in that it is a guaranteed time each week the president speaks to the populous. Therefore, it is ritualistic and occurs like clockwork every Saturday morning. Additionally, I selected the speeches randomly at the same points during each first year (for example randomly selecting the 9th, 15th, and 21st week speeches for all three presidencies). With close examination, I found several common traits that make this genre of presidential rhetoric unique compared to the inaugural, State of the Union, veto message, or farewell address just to name a few.

First, generic criticism asks what the underlying dynamic is that unites all the speeches. In this case, all the speeches have a prominent temporal element that signals the fleeting time of presidential action during an administration and the need for the president to document accomplishments, presidential acts, administrative protection and perpetuation of American values, and legislative successes and difficulties. Therefore, while time is the uniting characteristic and plays a prominent deictical role (in a linguistic

s sense), the speeches act as a mediated log of the presidency, a secular sermon that rehearses and recited communal values, and markers of Capitol time.

While citizens regularly think of a four or eight year span as an adequate amount of time to accomplish major change, the presidency must work within windows of time to push a comprehensive agenda. Upon taking office, a president has approximately 12 months before midterm reelection campaigns for members of Congress begin, which eliminates one year of a presidency for meaningful legislative action. Following the midterms, a president must begin gearing up for reelection as opponents traditionally mobilize. The president has another 6-8 months to move his agenda in the first term. Following this, everyone in Washington, D.C. has a campaign on the mind.

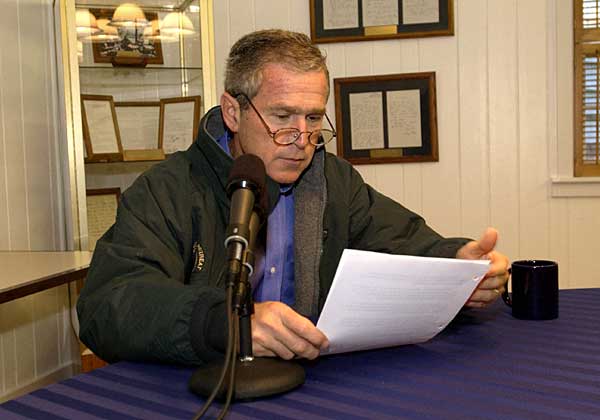

Within these time constraints, the weekly presidential address has become a mediated log of official presidential acts, travel, bill signings, and holidays. Clinton, Bush, and Obama used these speeches during their first year in office to report of “presidential” activities from traveling to Oregon for forest preservation (Clinton) to joining world leaders in Pittsburgh for the G8 (Obama). Additionally, presidents use holidays as a way to mark calendar time within a presidency while simultaneously relating present legislative and governing struggles to past American struggles, which segues to the second purpose for these speeches as a secular sermon.

When I say secular sermon, I am obviously referring to the weekly ritual of going to church and listening to the priest, minister, or rabbi’s weekly sermon/speech. A sermon usually rehearses and recites a certain set of religious values to uphold. Similarly, the weekly presidential address rehearses and recites American political values associated with national identification. This is most closely seen during holidays, when the president will use the 4th of July or Christmas for example to discuss the values embodied in that holiday, how they relate to the nation, and finally how they relate to his presidency and legislative proposals. The structure of these appeals follows closely to the one Eugene White laid out almost 40 years ago for the Puritan sermon. These appeals lay open the text or the meaning, explain the doctrine or truth, use reasons to back up the doctrine, and finally apply the sermon to everyday life.

Finally, presidents have used the weekly presidential address to mark Capitol time, specifically by praising or blaming Congress and bemoaning Washington political culture. We can see in this specific practice how presidents “go public” in Kernell’s sense, or go over the heads of Congress to directly advocate for popular action. By exhorting the people to call legislators or pressure Congress, presidents can also displace blame for failure to bring about political change. Additionally, in the process, they can also blame the culture of Washington and opponents who stall legislative action. Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama frequently talk of the culture of Washington either as opponents who obstruct or enjoy wastefully spending money. In doing this, the president can attempt to place himself above Washington antics while symbolically “fighting against the machine.”

Finally, presidents have used the weekly presidential address to mark Capitol time, specifically by praising or blaming Congress and bemoaning Washington political culture. We can see in this specific practice how presidents “go public” in Kernell’s sense, or go over the heads of Congress to directly advocate for popular action. By exhorting the people to call legislators or pressure Congress, presidents can also displace blame for failure to bring about political change. Additionally, in the process, they can also blame the culture of Washington and opponents who stall legislative action. Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama frequently talk of the culture of Washington either as opponents who obstruct or enjoy wastefully spending money. In doing this, the president can attempt to place himself above Washington antics while symbolically “fighting against the machine.”

I have begun to see that the Saturday presidential address, a genre of presidential rhetoric (at least a genre that I argue exists), plays an important sustaining role for the presidency while maintaining a similar thematic structure across administrations. With a framework in place, my next step is to examine whether the content of President Barack Obama’s speeches during his first year affirms or breaks with this general pattern based on the new medium of communication. As Marshall McLuhan said, “the medium is the message (or massage).” We will see if content has changed in the process as well as whether persuasive attitude change is different based on the medium.