Bandwagon vs. Authority: The Online Heuristic Revolution

Posted in The Gnovis Blog

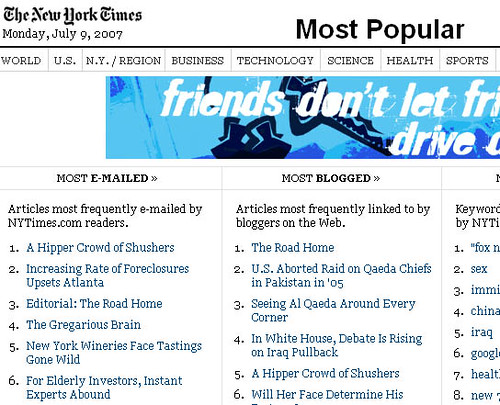

The most popular, recent, e-mailed, searched and blogged-about news stories of a given day are prominently displayed on nytimes.com and most online newspapers. To understand why this is so, one fundamental and foundational assumption must be made– that internet users genuinely care about what millions of other anonymous users think.

Judging from recent research on the bandwagon effect, that assumption may be stronger than expected.

The Web has become increasingly communal in its adolescence, and programmers have similarly developed increasingly complicated features for collecting and displaying ratings, recommendations, and opinions to other users. Research on e-commerce websites has shown that these ratings can indirectly affect purchase intention through opinion perception (see Sundar, Oeldorf-Hirsch, & Xu, 2008), and can even influence ratings of the quality, representativeness and credibility of online news stories (see Sundar & Nass, 2001).

When consistent, this bandwagon effect has been shown to be more powerful than competing appeals from experts or authority figures (Sundar, Oeldorf-Hirsch, & Xu, 2008; Sundar & Nass, 2001)- but that is not to say that experts and authorities have lost their touch.

Research on source credibility has proven the power of experts and authorities in changing opinion and behaviors. For instance, In business and commercial settings, audiences have more favorable attitudes toward experts, or products endorsed by experts, than toward non-experts or products endorsed by an unrecognized name. In a print journalistic setting, surveys have shown that editors often underestimate the amount of people who read their papers, the amount of time spent reading, and interest in hard news.

At least from the print editors’ perspective, there remains a hierarchical and necessarily dictatorial relationship between gatekeepers and their readers. On the Web, however, scholars have argued that the ability of non-expert or unknowledgeable readers to influence credibility ratings undermines the traditional authoritativeness of editorial experts. So which is it?

Ratings, recommendations and opinions from either peers or experts have been most often conceived of as cues that trigger mental shortcuts called cognitive heuristics (see Sundar, 2007).

When a Web site or news story is identified as coming from or recommended by an expert, the authority heuristic is cued (e.g. if an expert thinks this story is good, it must be good). Similarly, when a news story is ranked as the most popular, most blogged or e-mailed article of the day, the bandwagon heuristic is correspondingly cued (e.g. if other people think this story is good, it must be good).

Traditional methods of measuring the relative importance of print news articles – and an editor’s agenda – are rendered mute in online news.

Nevertheless, which cues are most powerful across media, and whether newspaper readers care that a story buried on two column inches of Page C23 of the New York Times is also the most blogged about story on nytimes.com, remains to be seen.